News:

DSC Prize for South Asian literature long-list announced. I’m disappointed that some big-name authors (of varying levels of mediocre) books have been included, as these threaten to overshadow the work of other lesser-known but very good authors. What I have liked about the DSC Prize in the past few years is its inclusion of a very wide variety of South Asian literature, from writing on South Asia by non-South Asian authors, as well as authors from and based in South Asia itself, originally written in English as well as translated into English. This is still evident in this long-list, but I hope the short-list is more discerning. And, now in its fifth year, I think it’s about time the top prize went to a woman, as it hasn’t yet, and South Asia is hardly short of female literary talent. Here’s the list.

And the Mountains Echoed, by Khaled Hosseini (read my review here)

The Lowland, by Jhumpa Lahiri (read my review here)

Helium, by Jaspreet Singh (review forthcoming)

The Gypsy Goddess, by Meena Kandasamy

Mad Girl’s Love Song, by Rukmini Bhaya Nair

The Mirror of Beauty, by Shamsur Rahman Faruqi (review forthcoming)

The Scatter Here is Too Great, by Bilal Tanweer

A God in Every Stone, by Kamila Shamsie (regular readers will know how I feel about Shamsie’s work, and this novel is no different as far as I’m concerned! I have reviewed it, along with Fatima Bhutto and Uzma Aslam Khan, in the latest issue of Himal Southasian)

The Prisoner, by Omar Shahid Hamid

Noontide Toll, by Romesh Gunesekara

Call for papers:

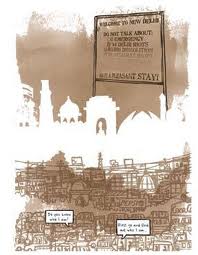

South Asian Popular Culture journal, special issue on ‘Graphic Novels & Visual Cultures in South Asia’.

Articles I’m reading this week:

‘Report: Panel discussion on “Conflict and Literature” held in India’, by Jaya Bhattacharji Rose, on Kitaab.

‘In the end, Pakistan champion Muhammad Iqbal had doubts about the Two-Nation theory’ excerpt from new book by Zafar Anjum on Iqbal, on Scroll.in.

‘Sufism: “a natural antidote to fanaticism”’ by Jason Webster, on the republication of an Idries Shah book about Sufism, on The Guardian.

‘Time for Peace’ by Salman Rashid, on the Asian Review of Books.

Events:

Mumbai: Tata Literature Live Festival begins this Thursday, 30th October.

Boston, New York, Austin, Houston, Los Angeles, Palo Alto, San Francisco: throughout November (starting on the 1st) Pakistani film Zinda Bhaag will be touring US universities, followed by q&a sessions.